The history of ancient India, particularly after the decline of the Mauryan Empire, witnessed significant transformations in its socio-economic structure. Among the most notable of these was the gradual emergence and Solidification of Feudalism, a system that fundamentally reshaped land ownership, social hierarchies, and the lives of ordinary people. While proto-feudal elements existed earlier, the true genesis of Feudalism in Indian society is generally marked from around 300 AD, with its characteristics evolving through different periods and culminating in the Rajput era.

Feudalism, in its essence, refers to a system of decentralized political and economic organization based on land tenure. It involves a hierarchy of lords and vassals, with the granting of land (fiefs) in exchange for loyalty, military service, and other obligations. In the Indian context, this meant the emergence of a powerful class of landed intermediaries who controlled vast tracts of land and exerted significant influence over the lives of the peasantry. While the idea of a monolithic "Indian feudalism" is an oversimplification, tracing its development provides valuable insights into the social, economic, and cultural dynamics of ancient India.

The economic basis for feudalism's rise in India was intrinsically linked to the growth of the agricultural economy. While agriculture was always a cornerstone of Indian civilization, its intensification and expansion during the Gupta and post-Gupta periods created the conditions for a landed elite to accumulate wealth and power. This process was further accelerated by the decline of long-distance trade, particularly after the reign of Harshavardhana in the 7th century AD. The disruption of established trade routes led to a contraction of urban centers and a shift in economic focus back towards localized agricultural production. This, in turn, amplified the importance of land ownership as the primary source of wealth and influence.

While vestiges of feudal-like structures can be observed in the post-Mauryan and Satavahana periods, the Pala-Pratihara-Rashtrakuta period (roughly 8th to 10th centuries AD) saw a significant consolidation of feudal tendencies. This era, characterized by regional kingdoms vying for power, witnessed the rise of landed intermediaries, often referred to as feudal lords or Samantas. These individuals were granted land by the rulers in exchange for military support and loyalty. They, in turn, extracted surplus from the peasantry, further solidifying their economic and political power.

A defining characteristic of this phase of feudalism was the expansion of the landed estates of these intermediaries. This expansion was often achieved through the resumption of ownerless lands (land held without clear ownership rights) and the infringement upon the traditional agrarian rights of the cultivating farmers. This process significantly altered the relationship between the state, the landlords, and the peasantry. Landlords became increasingly powerful, effectively functioning as local rulers within their domains.

Serfdom, or a system resembling it, became a significant feature of the Pala-Pratihara-Rashtrakuta feudalism. The freedom of movement and economic agency of the farmers was severely curtailed. They became tied to the land, obligated to work for the landlords, and subject to their arbitrary control. This erosion of peasant rights led to a decline in their living standards and a growing social stratification. The culture of the time also reflected this growing inequality, with artistic and literary expressions often glorifying the ruling elite and reinforcing the existing social order.

The feudal trends initiated in the Pala-Pratihara era were further solidified and, arguably, deteriorated in the subsequent Rajput period (roughly 10th to 12th centuries AD). The decentralized political landscape of the Rajput kingdoms, characterized by constant warfare and internecine rivalries, provided fertile ground for the consolidation of feudal power. The laws and regulations governing land tenure became stricter, further diminishing the rights and security of the tenant farmers.

In the Rajput feudal system, the tenant farmers progressively lost the security of their land tenure. They were often subjected to arbitrary evictions and exorbitant demands from the landlords. The economic condition of the common people deteriorated considerably, with many reduced to a state of abject poverty and dependency. The gap between the privileged elite and the vast majority of the population widened significantly. This had a profound impact on the social fabric, leading to increased social tensions and a heightened sense of exploitation.

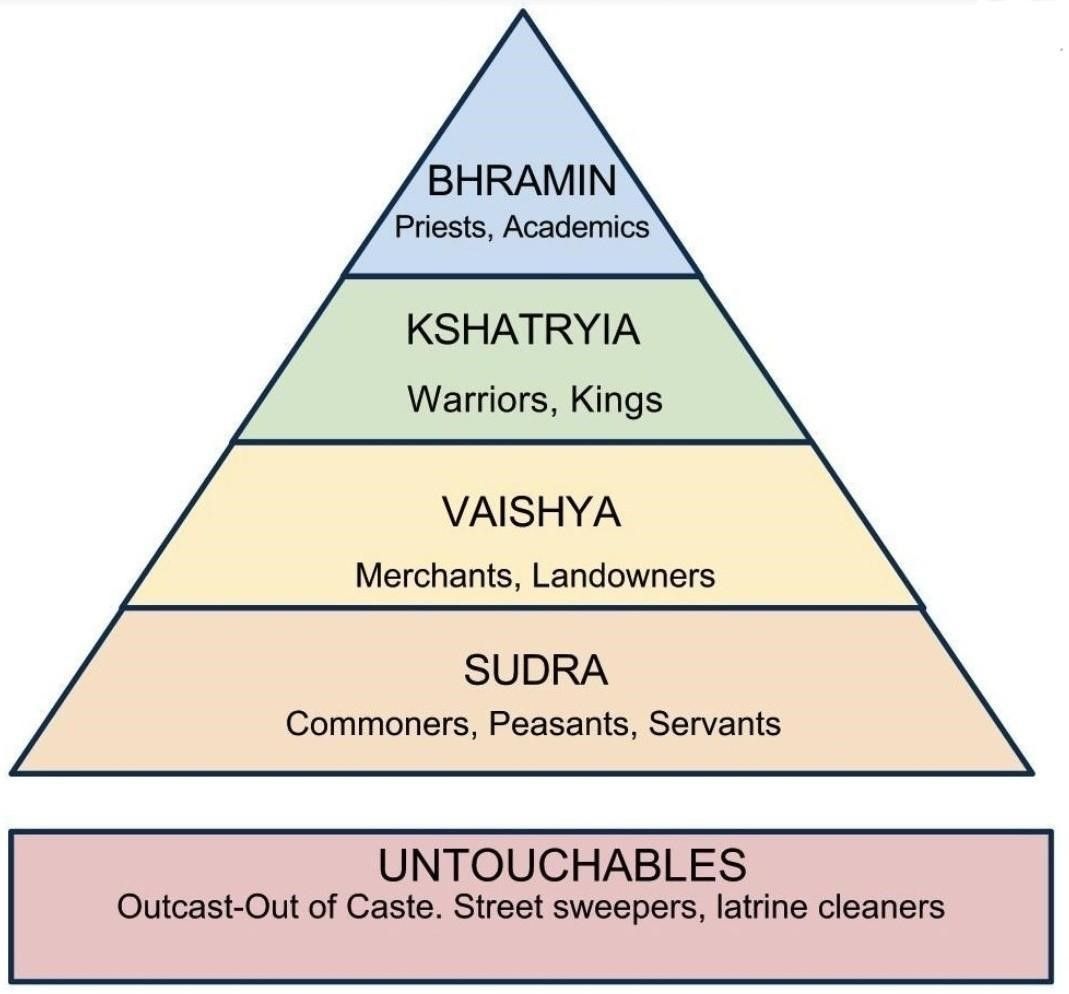

The culture of the Rajput period, while renowned for its valor and chivalry, also reflected the stark realities of feudal inequality. The bards and chroniclers often celebrated the heroic deeds of the Rajput warriors and the lavish lifestyles of the ruling class, while the plight of the common people remained largely unaddressed. The emphasis on caste hierarchy and rigid social stratification further reinforced the existing power structures and limited social mobility.

In conclusion, the genesis of feudalism in Indian society, beginning around 300 AD, was a complex and multifaceted process driven by economic changes, political fragmentation, and evolving social structures. From its early manifestations in the Pala-Pratihara-Rashtrakuta period to its more pronounced and arguably oppressive form in the Rajput era, feudalism fundamentally reshaped land ownership, social hierarchies, and the lives of ordinary people. The rise of landed intermediaries, the curtailment of peasant rights, and the increasing concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a select few had a lasting impact on the social, economic, and cultural landscape of Ancient India. Understanding the evolution of feudalism is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of Indian history and the complex interplay of social, economic, and political forces that shaped its trajectory.